Bill Taylor

Illusions Become Reality

My favorite memories of SMHS center around Buzz Clopper and the Drama department. I played medium-size acting parts in SMHS shows, (Anne Frank, Crucible, The Old Lady Shows Her Medals) worked various tech and crew positions on every other play (including my first effects work on stage) and met so many great people: Alan Freeman, Roger Pfaff, Sherry Proctor, Dolores Cordell (now my wife’s closest friend), Grant Gifford, Marty Udell, Rich Gerage, and so on and on.

The compelling fascination of my life has been visual illusion, both as entertainment in itself (you may remember me doing various kinds of stage and close-up magic) and in the service of story-telling, which turned out to be my career in movie Visual Effects.

Unlike everyone I know in the film world, I wasn’t interested in making movies as a kid; though I saw a lot of movies, the movie-making bug didn’t bite until I was 19 and at Pomona College.

I saw JASON AND THE ARGONAUTS (1963) on the big screen and was blown away. Ray Harryhausen’s miraculous combinations of animation and real actors seemed like magic on an enormous scale.

My college career sputtered to a halt after three semesters. It seemed unlikely I would set the world on fire as a magician or as a radio personality (I did college radio at Pomona) but the movie business seemed like a possibility.

I had previously introduced myself to a veteran in the movie Visual Effects field, Linwood Dunn, ASC. Lin gave me some great job-hunting advice: “Take a job, any job, even if it’s carrying someone’s briefcase. Just get in.”

Following his advice led to my first film gig at the Ray Mercer Company in Hollywood, a title and optical effects company with roots in the silent film era. I began as line-up tech, (transcribing workprint information and preparing count sheets and film rolls for the optical printer operators) and a part time delivery driver. Mercer’s got me into the Camera Union and moved me up to Camera Operator; in that job I shot optical effects, titles and product inserts on thousands of commercials, trailers and feature films. The experience in thinking of images combined in layers was invaluable.

I read everything I could find about image compositing and took a night class at USC’s Cinema Department, where I saw and heard the Color Difference blue screen system explained by its inventor, Petro Vlahos. (Until Vlahos’ revolutionary invention, “blue screen” shots often looked really dodgy, with black or blue outlines around the composited characters. Vlahos developed the techniques that made seamless shots possible, first in “Ben Hur”, then on films ranging from “The Birds” to “Mary Poppins”, and thousands of films since.) Vlahos became a friend, my life coach (a phrase unknown at the time) and my second mentor, a relationship that continues today. I became the Mercer Company’s resident blue screen expert.

After 11 years at Mercer, the USC connection paid off in several unexpected ways. A recently-graduated film major offered me the job of creating effects for a low budget film to be made in Brazil. The comfortable spot at Mercer was hard to leave, but I set out for Rio in the summer of 1973.

The film in Brazil collapsed in confusion after a month, and I returned to L.A., minus my equipment and without a job. A year of free-lance camera work followed at Lin Dunn’s company, Film Effects of Hollywood where I had the joy of working with Lin, Don Hendricks and the great Cecil Love.

Another USC film student, John Carpenter, had asked me to consult on his sci-fi thesis film, DARK STAR. When Carpenter and Dan O’Bannon decided to expand DARK STAR into a feature, I carried out the 16mm to 35mm blow-up, creating composite shots in the process. I also wrote the lyrics for the country-and-western title song, “Benson Arizona”.

Later the same year I was hired to work at Universal Studios’ Matte Department as the cameraman for another longtime mentor, the Oscar-winning matte artist Albert Whitlock, who I had met a decade earlier. My future business partner Syd Dutton came on board at Universal a month later.

The three decade friendship with Al Whitlock was easily the most important single influence on my career. I had originally met Al when I was working at Mercer’s. I had seen Al’s name on an innocuous comedy, “That Funny Feeling”, that had spectacularly effective shots that made the Universal back lot seem like it was in the middle of Manhattan. I called Al and introduced myself; he was willing to talk to a complete stranger about his work, and a few months later invited me to meet him at the studio. A decade later Al’s cameraman retired and he invited me on board.

Although I was no artist, thanks to Al I learned photography, composition and perspective from an artist’s viewpoint, and began to comprehend his profound grasp of what made a shot convincing.

THE HINDENBURG (1975), our first film with Whitlock, received the Oscar for visual effects. Suddenly I was in the big time. Universal promoted me to Director of Photography and I began to light and shoot many of the shots our department worked on.

Whitlock was a magnet for distinguished film-makers, and as a result we got to work on more than 100 films directed by everyone from John Huston (THE MAN WHO WOULD BE KING, UNDER THE VOLCANO), to Alfred Hitchcock (FRENZY, FAMILY PLOT) to Franklin Schaffner (PAPILLON).

When Al Whitlock retired in 1985, Syd and I founded Illusion Arts, Inc. Universal became one of our best clients. We eventually got screen credits on nearly 200 films, with a wildly diverse bunch of directors: among them Martin Scorcese (CAPE FEAR, THE AGE OF INNOCENCE), John Landis (THE BLUES BROTHERS, COMING TO AMERICA, INNOCENT BLOOD), and Mike Nichols (THE BIRDCAGE).

Later, I served as on-set visual effects supervisor on THE FAST AND THE FURIOUS (2001), BRUCE ALMIGHTY (2003), and my all-time favorite, Lasse Hallstrom’s CASANOVA (2005), which sent me to Venice for six weeks. Later still, Syd and I co-supervised MILK (2008), our 6th film for director Gus Van Sant, for which we created more than 150 “invisible” shots. As Illusion Arts wound up its 26 year run, our company completed dozens of shots for Michael Mann’s PUBLIC ENEMIES (2009) for supervisor Robert Stadd and some key environments for GI JOE (2009).

I also did various gigs as as second unit or models unit Cinematographer for DAYLIGHT (1996), CLOCKSTOPPERS (2002), SERENITY (2005), THE NANNY DIARIES (2007), RAMBO (2008), and SOUL MEN (2008).

My most recent credits as Visual Effects Supervisor are for John Hillcoat’s LAWLESS (2012), and Brandon Hess’ AFI film for the National Air and Space Museum, FIRST IN FLIGHT.

I am the co-author (with Petro Vlahos) of the chapters on blue-screen and green-screen compositing in both the “American Cinematographer Manual” and the “Visual Effects Society Handbook”.

In 1972, Petro Vlahos and the late Pete Clark endorsed me for membership in the Motion Picture Academy. Like any other mostly-volunteer organization, the Academy can take as much of your time as you are willing to give.

I was recruited into the Science and Technology Awards Committee, where I have served (with a few breaks) ever since. I was the founding co-chair of the Academy Science and Technology Council, and served 5 terms as an Academy Governor representing the Visual Effects Branch, and chaired the Executive Committee. Closing a couple of circles very nicely I had the pleasure of presenting two Academy programs honoring my inspiration Ray Harryhausen, and a program honoring my mentor Petro Vlahos.

I’ve had the good fortune to have received a Saturn Award, an Emmy and a Motion Picture Academy Technical Achievement Award. I’m a Founder and Honorary Life Member of the Visual Effects Society, and the recipient of the 2009 Founder’s Award and a 2012 Fellowship in the Society. In a slightly surreal event, my former partner Syd and I were granted honorary “Doctor of Humane Letters” degrees from the Academy of Art University in San Francisco.

In 2011 Syd and I received the “Creative Imagery” award from the Art Directors’ Guild, and in February I will receive the “John Bonner Medallion” from the Academy.

My SMHS speech and drama training has not been entirely wasted. I’ve had quite a few speaking gigs at the USC and UCLA film schools and at the American Film Institute, and I’ve given talks for the Society of Optical Engineers, the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers, the National Film Board of Canada, and the Entertainment Imaging Conference in Kanazawa, Japan. I twice served as the Host/Preenter of the Visual Effects Theater at ShowBiz Expo. In 2012 I stood in for my friend Richard Edlund as Keynote Speaker at the KOCCA Conference in Seoul, Korea.

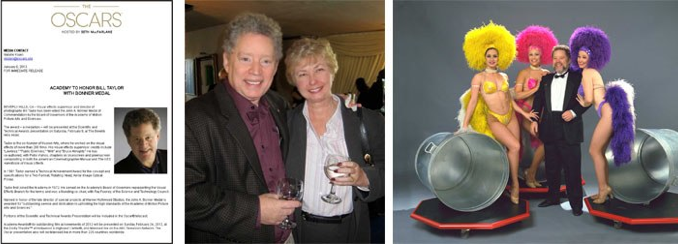

While I now perform magic only for the fun of it (it was once an important part of my living) I continue to create large- and small-scale magic for professionals around the world. My stage illusions featured in the shows of the late Harry Blackstone Jr., the late Doug Henning and Tihany, and more recently in Las Vegas shows by The Ferco Brothers, The Pendragons, The Gamesters, Harry Anderson, and many other performers both renowned and exceedingly obscure. My best-known illusion is a giant version of the classic three-shell swindle called “Trash Can Monte”. In performance, the audience can’t quite follow under which can a beautiful woman is hiding. In the climax to the effect, three different women appear unexpectedly. A promo photo for this might be the funniest photo of my life, which is attached to this bio.

I’ve done a lot of still photography outside the movie business . My photos illustrate books on sleight of hand, magic performance, and the allied arts by John Carney, Earl Nelson, Frank Simon, Harry Anderson, Mike Caveney and other names well-known in the tiny, close-knit magic world. Steve Forte’s “Casino Game Protection” (2004) and “Poker Protection” (2006) are the authoritative books about cheating at games of chance, featuring hundreds of my color photos.

With my pal Mike Caveney I co-published the definitive version of S.W. Erdnase’s “The Expert at the Card Table”, a classic 1902 book on sleight-of-hand cheating and card manipulation. Our edition, called “The Annotated Erdnase”, appeared in 1999 with extensive notes and commentary by the present-day expert Darwin Ortiz; it is now in its fifth edition.

Also in 1999, I produced, directed and photographed a joint venture with Mr. Ortiz, a one-hour video documentary titled “Darwin Ortiz on Card Cheating”. In addition to selling thousands of copies, it has been pirated around the world; a Russian-language trailer can be found on “YouTube”.

(In spite of my fascination with card cheating, I hasten to note that I don’t play cards or any other games, and have never wagered on any event, contest or proposition. I did lose a quarter once in a slot machine, a traumatic event.)

Beginning at SMHS, I’ve played at design in several fields. In addition to designs for magic props and movie graphics, I’ve done odd bits of furniture, clock cases, and dozens of pieces of jewelry. Examples of this work and some gallery photography appeared in the Visual Effects Society’s volume of members’ personal art, “Vesage” (2009).

In my spare time, I collect and photograph unusual clocks. In 2005 I partnered with the British Horological Institute (BHI) to co-publish “Woodward on Time”, an annotated edition of the collected papers of an eminent British scientist, Philip Woodward. (Quite apart from his work in horology, Dr. Woodward was one of the inventors of radar, and a pioneer of computer science and statistical mathematics.) Probably because of the book, I was made an Honorary Fellow of the BHI in 2007.

A coffee-table book of my clock photographs, “The Art of Pierced Brass”, was published in 2012 by the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors.

Other interests include live concert music, particularly an eclectic bunch of 20th century composers.

After two laughably short and unsuccessful marriages, I finally wised up and married my attorney, Kay Henden, who I met at Pomona in 1964. She has striven mightily to keep me out of trouble. We celebrated our tenth wedding anniversary in December 2012, a personal best for us both.

So it’s been quite an adventure, and it seems to be continuing! The movie business has taken me all over the world and allowed me to know and work with some great artists. I have no intention of quitting; as the great Production Designer Henry Bumstead (the father of our classmate Ann) said while he was working on “The Pacific” in his 80’s, “You’ll know you’re retired when they stop calling.”

Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences press release announcing Bill Taylor being honored with the Bonner Award, February 2013. Bill and Kay Taylor. Trash Can Monte illusion finale, Las Vegas.